|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

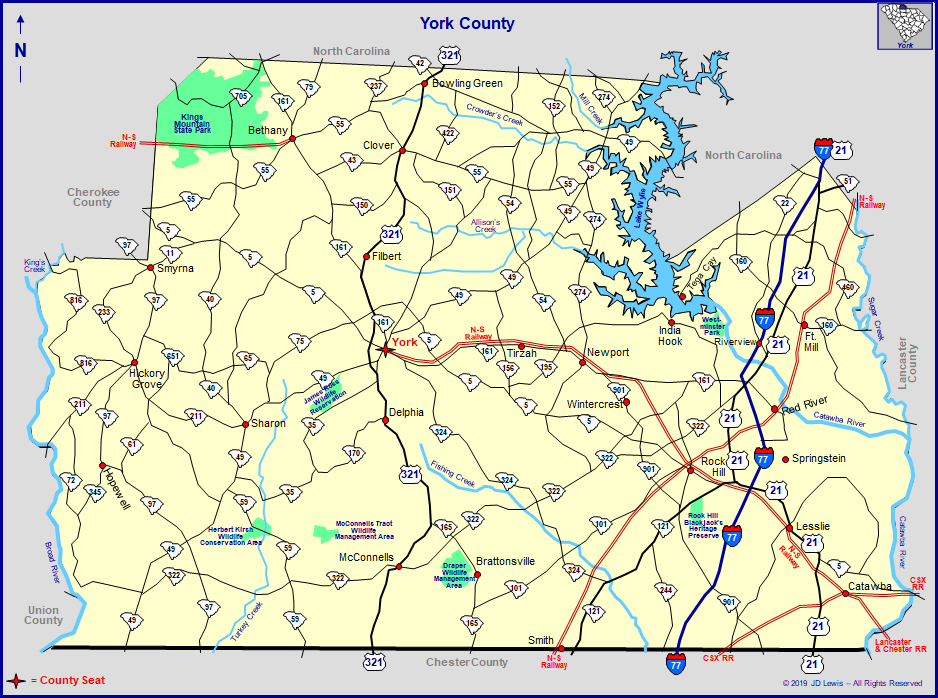

Presbyterian Church - York County, South Carolina Click Here to learn about the two "Street Railways" that operated in Rock Hill from 1901 to 1918. York County is located in the north-central portion of South Carolina and is bordered by the state of North Carolina to the north, Chester County to the south, Lancaster County to the east, and Cherokee and Union counties to the west. Natural boundaries include the Broad River on the west and the Catawba River on the east. All of York County is located within the piedmont, a one hundred mile wide belt of land extending from the sand hills of northeastern South Carolina to the Blue Ridge Mountains in the state's northwestern corner. The piedmont is characterized by varied terrain, ranging from rolling hills in the southeast to very steep hills in the northwest.(1) York County is heavily wooded in many rural areas, as evidenced by the significant role played by the timber industry in today's local economy. Cotton, historically the dominant crop,(2) is still grown, though not to as great an extent as in the past. York County still retains a predominantly rural character, the major exception being the county's eastern third. This section includes Rock Hill, which is by far the largest city, as well as the smaller towns of Fort Mill, and Tega Cay, along with growing residential development along Lake Wylie. Much of the growth of northwestern York County is due to increasing development pressure from nearby Charlotte, North Carolina. Many think of York County's history as beginning in the 1770s shortly before the American Revolution, but by that time the area was well on its way to developing a rich heritage. In the 1540s, Spanish explorer Hernando DeSoto passed through the area in his search for gold, which eventually led to his death on the banks of the Mississippi River. Following DeSoto came Juan Pardo. Pardo entered what is now York County during his travels through South Carolina in the late 1560s and recorded his observation of a predominant Indian tribe, later confirmed to be the Catawba, in the vicinity of present-day Fort Mill on the eastern bank of the Catawba River. Before DeSoto, Pardo, and other Europeans arrived, the area was the domain of the Catawba Indians, a band of Siouan speakers numbering about 6,000 at the time of the first European contact.(3) Primarily agriculturists, the Catawbas gave much assistance and support to their new neighbors. The colony of South Carolina began in 1670 when British settlers under the sponsorship of eight (8) Lords Proprietors planted a settlement near present-day Charleston. From the Charles Town settlement (named after King Charles II) on the South Carolina coast, the eight Lords Proprietors established one of the early British colonies south of the Chesapeake Bay. Twelve years later the colony was divided into three counties for administrative purposes. Craven County, encompassing roughly the northern half of South Carolina, included the land which would eventually become York County. Allied by blood and religious affiliations, the Scots-Irish sought to escape a hard life in Ulster of Northern Ireland by migrating to the American colonies. The first European settlers in the Carolina piedmont, or backcountry as it was called, were these Scots-Irish Presbyterians. In order to rid themselves of the ever-increasing rents and land prices in Pennsylvania, and with the opening of new and more fertile lands to the South where they would be free to practice their Calvinistic brand of religious beliefs, these Scots-Irish Presbyterians migrated southward. Coming predominantly from former homes in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina down the "Great Wagon Road," these early pioneers began arriving in the region west of the Catawba River during the mid to late 1740s and eventually drifted into what would later become York County in the 1750s. Prior to the establishment of a dividing line between the two Carolinas, the area to become York County was part of Bladen County, North Carolina. In 1750, it was included in the newly-created Anson County, NC. The first land grants and deeds for the region were issued in Anson County, North Carolina. The Carolina backcountry was nearly devoid of European settlers prior to 1750, but by the time the American Revolution reached the area in 1780, the backcountry contained an estimated population of more than a quarter of a million.(4) The largest proportion of these were Scots-Irish Presbyterians,(5) although there were also numbers of English, Welsh, native Irish, native Scots, Swiss, French, and Germans.(6) By 1760, the whole Carolina backcountry was ablaze with activity caused by the migrations. Two years later, Mecklenburg County, NC was cut from the western end of Anson and included the lands of present-day York County. The area next became part of Tryon County in 1768 when the colonial General Assembly of North Carolina set aside all the land west of the Catawba River and south of Rowan County. The York County area would remain a part of Tryon County until 1772, when the boundary line between North and South Carolina was finally established and formally surveyed. From 1772 until the end of the Revolutionary War, the area was known as the "New Acquisition District" and ran approximately eleven miles north-to-south and sixty-five miles from east-to-west. Finally in 1785, York County became one of the original counties in the newly-created state. Its boundaries at the time of creation have remained unchanged to the present day with the exception of a small area in the far northwestern corner of the county (originally Cherokee Township), separated in 1897 and included in the formation of Cherokee County. The first European settlers in the region migrated into York County from the east, northeast, and southeast by way of Mecklenburg, Lancaster, and Chester counties. They settled in a dispersed community pattern denoted by its communal, clannish, family-related groups known as "clachans," much the same as they had in Pennsylvania and Ulster. The clachans developed around the Presbyterian Kirks, or meetinghouses, and became the forerunners of the congregations.(7) These congregations generally encompassed a five-to-ten-mile radius centered on the meetinghouse, and contained anywhere from 20 to 500 families.(8) The church, therefore, became the focal point of backcountry society, and around these churches settled the new residents of the region, eventually creating the present-day congregations. In York County, the "Four B" churches (all Presbyterian) of Bethel, Bethesda, Beersheba, and Bullock Creek became the first religious and social centers in this Scots-Irish stronghold. For purposes of self-defense, the settlers of the backcountry began military drilling soon after they entered the region. Finding themselves sandwiched in between unfriendly natives to the west, (primarily in the form of Cherokee, Shawnee, and Creek) and indifference on the part of English officials in Charlestown, who considered residents of the backcountry uncivilized, the early settlers frequently found themselves the targets of Indian raids. In a region so often ignored, the local militia became an early police force, patrolling the area for possible Indian or slave troubles and controlling the seemingly numerous outlaw bands which roamed the region.(9) The militia system in the backcountry was born of necessity. Militia units, or "Beat Companies," enrolled every able-bodied man on the frontier.(10) Although the militia system gave some limited military training to the men of the county, it never developed enough to enable it to wage an all-out war. The one advantage, however, which the militia systems brought to the area was their social organization. This organizational base contributed to the state's ability to fight for the next hundred years. As the American Revolution in the South approached, militia service became instrumental in turning the tide of war against the British. The section of South Carolina known as the "New Acquisition District" was the scene of significant activity during the war. The battles of Williamson's Plantation (aka Huck's Defeat) and Kings Mountain, among others, were fought on York County soil. At first, however, the residents of the backcountry did not readily take sides in the conflict. They were content to remain neutral as long as they were left alone. Most of the backcountry approached the war with the attitude that the conflict was between the British Crown and Charlestown aristocrats and, as such, did not concern them. The people of York County entered into vocal opposition to Royal authority in 1780 after three "invasions" of the region; first by Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton and his "Green Dragoons," and subsequently by Lt. General Charles, Lord Cornwallis on two separate occasions. After the British capture of Charlestown and Buford's Massacre in Lancaster County in May of 1780, most of the state's population cowered or capitulated to British designs. While British terms and paroles were accepted across the state, the residents of the backcountry continued a regional resistance, led by men such as William "Billy" Hill, William Bratton, and Samuel Watson. Lord Cornwallis was persuaded to look more northward for salvation instead of this "nest of hornets" in which he found himself. The American Revolution in the backcountry brought great economic hardship, but it also brought new opportunities, particularly in the role of increased self-government. The residents of the backcountry, having played a significant role in the defeat of Loyalist forces within the state, enjoyed a greater share in the voice of administration in their region following the war. The entire backcountry experienced phenomenal growth as huge numbers of new residents crowded into the region during the 1780s. An act of the South Carolina General Assembly established York County in 1785. In the first census of the United States, taken five years later, York County contained a population of 6,604. This population, however, was not of the "planter class" that so many people raised on "Gone With the Wind" identify. Of those 6,604 counted in 1790, 923 were listed as slaves, and one-quarter of these belonged to just nine men. York County had less than 15% of its population living in bondage in 1790, while the state averaged around 30%.(11) Steps to establish a county seat were first taken in 1786 with the laying out of a town on the site of Fergus' Cross Roads. The name of the crossroads originated with two brothers, John and William Fergus,(12) and was the crossing of six roads near the geographic center of the county (near the present location of Congress and Liberty Streets in York). The six routes were important wagon roads; one running northwestward from the village of York toward Kings Mountain known as the Rutherford Road, one running southwestward toward Pinckney's Ferry on the Broad River, one running south to Chesterville, one running northeastward toward Charlottesburg and the Catawba River known as the Armstrong Ford Road, one running eastward towards Nation Ford on the Catawba River, and the sixth running southeastward to Landsford on the Catawba River in Chester County. The new town became known as the village of York, or more commonly York Court House within a few years. In 1841, when the town was incorporated, the name officially became Yorkville. Nearly all of the original lots were sized with a width (or street frontage) of 66 feet and a depth of 330 feet. A public spring was established and utilized by the early residents as a source of drinking water and for washing clothes.(13) In 1800, South Carolina renamed all counties as districts, a term it would use until after the American Civil War. William D. Martin, a future member of the South Carolina House of Representatives, traveled through the village of York in May of 1809, and gave a description of the town in his journal. "Its local situation is pleasant & interesting. The scite [sic] is on a plane of some length, near the centre of which is a small eminence, on which is built the Court House, a neat brick building. The private houses also, are principally of brick, & very far excel those usually built in similar places."(14) The population of the village in 1823, as recorded by Robert Mills, stood at 441 and included 292 whites and 149 blacks. In his Statistics of South Carolina, Mills provides us with a good view of the village of York in 1826. The town was "regularly laid out in squares" containing "8 stores, 5 taverns, a male and female academy, post office, and a printing office, which issues two papers weekly." Brief descriptions are also given of the new court house, the public jail, and several residences. Mills concluded that the village at that time had a bright future. "The increasing prosperity of this village, its salubrious site, interesting scenery, contiguity to the mountains, and cheapness of living, will have a tendency to give it a preference in the minds of those who are seeking residence in the upper country."(15) By 1840, the population of the town had reached 600; by 1850, Yorkville contained 93 dwellings and 617 inhabitants.(16) In the years just prior to the American Civil War, the town gained a reputation as a summer resort for many lowcountry planters trying to escape the malarial swamps of the lowcountry for the moderate climate to be found in the upstate. By 1860, the population of the town had topped 1,300, an increase of more than 125% in only one decade.(17) During the Civil War, the town also became a focal point for residents from the lowcountry as a refugee destination during Federal occupation of their hometowns. York District as a whole experienced significant growth during the antebellum years, and the increase occurred primarily among the black population. With the introduction of the cotton gin in the 1790s, the county's future was established. As the importance of "King Cotton" grew, so too did slavery become an integral part of the economic life of the county. The cotton boom, which had a tremendous impact on the entire southeast, greatly influenced agriculture and slave holding patterns in the South Carolina backcountry, including York District. In 1793, all of South Carolina produced only 94,000 pounds of cotton, and most of this was grown in the Sea Islands. In 1811, however, the backcountry alone accounted for over 30 million pounds.(18) Obviously, cotton production greatly changed life on farms throughout the South Carolina backcountry. While in 1800, 25% of all white families in the backcountry owned slaves, by 1820 nearly 40% of the families were slaveholders.(19) Slave ownership increased significantly in York District between 1800 and 1860, though most slaves worked on small and medium sized farms rather than large plantations. In 1800, whites made up 82.1% of the total population in York District, indicating that slave ownership had yet to become common. By 1820, however, the white population accounted for only 68.6% of the total, indicating that the institution of slavery had taken hold, and by 1860 the white percentage of the county's total population dropped to 62.5%.(20) York District figures from 1860 reveal that slave holdings were relatively small, with approximately 70% of all farms holding fewer than 10 slaves and less than 3% of the farms holding 50 or more.(21) Nearly 20% of all York District farms in 1860 had less than 50 acres of land, 23.9% contained from 51 to 100 acres, 53.9% ranged from 101 to 500 acres, and only 2.7% had over 500 acres.(22) The average number of improved acres of York District farms in 1860 stood at 153.3.(23) These figures substantiate the premise that York County was primarily a region of small and medium-sized farm operations during the antebellum period. Although some large plantations existed in York District, they were not the norm. Twenty short years following the first census, York District had increased in population to more than 10,000 - of which over 3,000 were slaves. As the county's dependence on cotton grew, its dependence on slave labor to produce the crop also grew. By 1850, York District topped 15,000 residents, over 40% of which were slaves.(24) On the eve of the Civil War, the county's population grew to approximately 21,500 with almost half of the population enslaved labor.(25) During this period York District was heavily tied to agriculture, with 93% of the work force involved in raising crops in 1850; this at a time when the rest of the United States averaged a 78% agricultural work force. Only 13% of the York District population was involved in industry of one form or another.(26) The antebellum period saw the establishment and growth of several rural settlement areas and communities in York District. In 1825, only three post offices were in operation in all of York District, at Yorkville, Blairsville, and Hopewell.(27) By 1852, however, York District contained 27 post offices, a clear sign that the county was becoming increasingly settled. A fairly extensive system of roads was also in place by this time.(28) Signs of growth and prosperity from the early nineteenth century can be seen in the establishment of York District's first newspaper, The Yorkville Pioneer, in 1823. Although this publication was only in operation for slightly over a year, it was followed by several others, including The Patriot, The Whig, The Journal of the Times, The Yorkville Compiler, The Yorkville Miscellany and, in 1855, The Yorkville Enquirer, which remains in publication today.(29) A major factor in York District's mid-nineteenth-century growth was the arrival in the eastern part of the county of the Charlotte & South Carolina Railroad, opened in 1852. While construction progressed on the Charlotte & South Carolina Railroad, residents of Yorkville and western York District realized they would also benefit from rail access. Chartered in 1848, the Kings Mountain Railroad Company began construction of a connecting line between Yorkville and the Charlotte & South Carolina Railroad at Chester. This track was completed in 1852. The resulting rail service provided a great economic boost to York District, bringing new goods, offering an easy source of transportation for the county's agricultural products, and even adding additional employment opportunities. Rock Hill, located on the Charlotte & South Carolina Railroad, rapidly developed as a transportation center in eastern York District, and yet by 1860 it contained no more than 100 residents and remained little more than a crossroads settlement.(30) Education played an important part in the lives of the early residents. Stemming from the great importance placed upon education by the Scots-Irish Presbyterians, numerous schools operated within the county prior to the American Civil War. More than a dozen academies were operating at the outbreak of hostilities.(31) These academies flourished throughout the county and provided instruction in a variety of subjects, including reading, writing, and arithmetic, as well as geography and rhetoric. The most famous was the Kings Mountain Military Academy in Yorkville, founded in 1854 by Micah Jenkins and Asbury Coward.(32) On the eve of the war, York District was one of the more populated districts in upstate South Carolina. The 1860 white male population of York District was just over 5,500.(33) When war broke out, the men of the county rose to the support of the Confederate cause in numbers large enough to create fourteen infantry companies (not to mention many more who saw service in different cavalry and artillery regiments, and those that joined outside the county). The companies formed had colorful names: Jenkins' Light Infantry, Whyte Guards, Carolina Rifles, Kings Mountain Guards, Catawba Light Infantry, Bethel Guards, Lacy Guards, Indian Land Guards, Palmer Guards, Campbell Rifles, Turkey Creek Grays, Indian Land Tigers, Mountain Guards, and the Broad River Light Infantry. Ebullient about a quick and glorious victory over the "invader," many of these men would pay a heavy price for their support of the Confederacy. During the war, York District would have the highest death rate of any county in South Carolina.(34) Even though only one (minor) battle was fought during the Civil War in York District (the battle for the Catawba Bridge at Nation Ford in 1865), the war caused a great upheaval in the county that was not soon overcome. Growth was halted, and in fact Yorkville itself actually contained fewer residents in 1880 (1,339) than it had in 1860 (1,360).(35) Gradually, however, signs of recovery appeared. With the new state Constitution of 1868, all districts were renamed as counties. Therefore, York District became York County once again (as it was from 1785 to 1800). Though York County never developed a plantation economy to match that of the lower piedmont and the state's coastal region, Reconstruction did bring changes to established agricultural patterns. Many of York County's larger property owners were forced to sell off portions of their land to smaller farmers, for without slave labor they could not productively work such large land holdings. As a result, the size of the average farm in York County dropped considerably while the number of small farming operations increased.(36) Late-nineteenth-century agriculture in York County, as in much of South Carolina and the southeast, was characterized by relatively small farm operations and ignorance concerning soil qualities and the benefits of diversification. As a body of knowledge emerged concerning scientific farming practices, advocates of diversification urged farmers to avoid relying on a single crop (typically cotton) and instead plant a variety of crops and raise livestock. This advice was generally ignored, contributing to the agricultural difficulties of the 1920s and 1930s.(37) The post-Civil War economy in York County, as in much of South Carolina, was characterized by an expanding transportation network and growth in the commercial and industrial base. The railroad played a major role in bringing York County out of its post-war economic decline. In 1872, a plan was developed for the construction and extension of the Kings Mountain Railroad. The Carolina Narrow Gauge Railroad Company was incorporated in North Carolina, followed by the incorporation of the Chester & Lenoir Narrow Gauge Railroad in South Carolina in 1873. The Chester & Lenoir was authorized to construct a narrow gauge railroad from Chester through Yorkville and on to some point on the North Carolina-South Carolina line, thus consolidating the Kings Mountain Railroad with the Carolina Narrow Gauge and bringing rail service to western York County. On the other side of the county, the Charlotte & South Carolina Railroad's bridge over the Catawba River was replaced and allowed the Rock Hill vicinity to begin economic recovery. The eventual revival of the cotton market through technological advances was another reason why York County recovered from economic devastation brought by the Civil War. In 1880, the establishment of the Rock Hill Cotton Factory (the first steam-powered cotton factory in South Carolina) ushered in a new era of agricultural expansion and, even more significantly, industrial development. The Rock Hill Buggy Company, founded by John Gary Anderson, originally began as a small operation and eventually grew to become the highly successful Anderson Motor Company, the first automobile manufacturing facility in the South.(38) Rock Hill experienced profound growth between 1880 and 1895, its population rising from 809 to over 5,500.(39) Since 1900, York County has continued the pattern of growth begun around 1880, but with one obvious and rather extended exception. This was a period of decline initiated by the failure of the cotton industry in the early 1920s; the Great Depression of the 1930s thus continued the county's stagnation. Between 1900 and 1920 York County's population increased from 41,684 to 50,536; a 21.2% increase. By 1930, however, the population total had only risen to 53,418, or a 5.7% increase. By 1940, the figure stood at 58,663, a 9.8% increase.(40) Cotton production remained the dominant agriculture in early 20th century York County, and the textile industry continued to develop. Rock Hill became the hub of this industry, while mills blossomed throughout the county. South Carolina's peak cotton crop was harvested in 1921; thereafter, cotton production began a long, steady decline. There were several factors involved, the most important being destruction caused by the boll weevil and soil erosion resulting from years of overuse. In 1918, an all-time high of 49% of the state's cultivated land was planted in cotton; by 1938 cotton accounted for only 10%. New Deal programs of the 1930s prodded farmers into switching to crops such as soybeans, which actually improved soil conditions.(41) York County saw a similar process, as cotton gradually became less and less important to the economy during the 1920s and 1930s. The late nineteenth and early twentieth century trend toward smaller farming operations was reversed, resulting in the smaller communities no longer playing such an important role in offering services to farming families. As a consequence, these communities have declined or disappeared. One of the most important developments in twentieth century York County was the 1904 completion of Catawba Dam and Power Plant, primarily due to the efforts of William C. Whitner. In 1899, Whitner founded the Catawba Power Company along with Dr. Gill Wylie and his brother Robert Wylie. Construction on the dam began in 1900, but the vastness of the project combined with periodic flooding made progress excruciatingly slow. When finally completed, however, the dam and power plant constituted one of the most important engineering accomplishments in the southeastern United States. The venture resulted in the eventual establishment of the Duke Power Company, and a series of dams and hydroelectric facilities were subsequently constructed on the Catawba River in both North and South Carolina. The Catawba Power Plant itself is credited with sparking the industrialization of the Catawba Valley, as by 1911 more than a million textile spindles were being powered as a result of this one plant.(42) Regardless of Rock Hill's development into a mid-sized city, the ever-increasing developmental pressure being exerted by nearby Charlotte, North Carolina, and the decline of small-scale farming, much of York County remains rural in character and has held on to a good measure of its historic integrity. The county seat of York remains a small town, clearly expressive of its lengthy history, while several other smaller communities and many of the rural areas offer confirmation of York County's developmental periods through their remaining historic structures and sites. FOOTNOTES: 1). Charles F. Kovacik and John J. Winberry, South Carolina: A Geography (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1987), 16-17. 2). Lacy K. Ford, Origins of Southern Radicalism: The South Carolina Upcountry, 1800-1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 246. 3). James Mooney, The Siouan Tribes of the East, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895), 71-73. 4). Gaius Jackson Slosser, ed., They Seek a Country: The American Presbyterians (NY): The Macmillan Company, 1955) 66; John Solomon Otto, The Southern Frontiers, 1607-1860 (NY: Greenwood Press, 1989) 65. 5). Prior to the American Revolution, of the 37 earliest churches founded in an 18 county region of the Carolina Piedmont stretching from Rowan County, North Carolina to Fairfield County, South Carolina, 31 were Presbyterian. By 1850, Presbyterians would still be the most dominant religious group in York County, claiming 46% of the county's church-going population; Arnold Shankman, et al, York County, South Carolina: Its People and Its Heritage (Norfolk, VA: The Donning Company, 1983) 36. 6). Dr. David Bigger quoted an earlier historian as to the ethnic makeup of York County on the eve of the Revolution as being, "Scotch 70 per cent; English 20 per cent; the other 10 per cent composed of Welsh, Huguenot and native Irish. The native Irish constituted less than 1 per cent." Evening Herald, 30 October 1931. 7). Otto, Southern Frontiers, 65. 8). Slosser, Seek a Country, 68. 9). This vigilante type of justice system was evidenced by the "Regulator Movement" of the South Carolina Backcountry from the mid 1760s to early 1770s. For more information on the Regulator Movement in the South Carolina Backcountry see, Richard Maxwell Brown's "The South Carolina Regulators." 10). Michael E. Stauffer, South Carolina's Antebellum Militia (Columbia, SC: South Carolina Department of Archives & History, 1991) 2. 11). Shankman, York County, 19. 12). William Boyce White, Jr., Genealogy of Col. William Hill of York County, S.C. (York, SC: Yorkville Historical Society, 1993) 2. 13). John R. Hart, "History of the Town of Yorkville" [unpublished manuscript] (York, SC: Historical Center of York County) 8. 14). Anna D. Elmore, ed., The Journal of William D. Martin (Charlotte, NC: Heritage House, 1958) 7. 15). Robert Mills, Statistics of South Carolina, Including a View of Its Natural, Civil, and Military History, General and Particular (Charleston, 1826) 771-782. 16). York County, South Carolina, Population Schedules of the Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Roll 860 (Washington, DC: National Archives Publications). 17). 1,360; South Carolina State Board of Agriculture, Hamonds Handbook of South Carolina (1883) 1. 18). Ford, Origins, 7. 19). Ford, Origins, 12. 20). David Duncan Wallace, South Carolina: A Short History, 1520-1948 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1961) 710. 21). Sam Bowers Hilliard, Atlas of Antebellum Southern Agriculture (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1984) 41-42. 22). Ford, Origins, 49. 23). Ford, Origins, 250. 24). 1850 Census of the United States of America: York District, South Carolina. 25). York County, South Carolina, Population Schedules of the Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, Roll 1228 (Washington, DC: National Archives Publications). 26). Shankman, York County: 24; Ford, Origins, 50. 27). The Hopewell community is now located in present-day Cherokee County. Harvey S.Teal and Robert J. Stets, South Carolina Postal History and Illustrated Catalog of Postmarks, 1760-1860 (Lake Oswego, OR: Raven Press, 1989) 113. 28). Teal and Stets, SC Postal History, 113. 29). For a complete listing of newspapers published in York County throughout its history, see John Hammond Moore, South Carolina Newspapers (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1988). 30). Rock Hill School District No. 3, We the People; A Study of the Processes of Local Government as Exercised at Rock Hill, York County, South Carolina (Rock Hill, SC: White Printing Company, 1970) 11-12. 31). United States Census, Social Statistics Schedules for South Carolina, York District, 1860. 32). Soon after their graduation from the Citadel, prior to the war, Jenkins and Coward came to Yorkville and began a private military school. 33). 1860 Census of the United States, York District, South Carolina. 34). Randolph W. Kirkland, Broken Fortunes (Charleston, SC: South Carolina Historical Society, 1995). 35). S.C. State Board of Agriculture, Hammond's Handbook, 1. 36). Jerry Lee West, A Historical Sketch of the People, Places and Homes of Bullocks Creek, South Carolina (Richburg, SC: Chester District Genealogical Society, 1986) 24. 37). Gilbert C. Fite, Cotton Fields No More: Southern Agriculture, 1865-1980 (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1984) 68-69, 82. 38). Douglas Summers Brown, A City Without Cobwebs (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1953) 188-189. 39). Brown, City Without Cobwebs, 168. 40). Wallace, South Carolina, 711-712. 41). Lewis P. Jones, South Carolina: A Synoptic History for Laymen (Orangeburg, SC: Sandlapper Publishing Company, Inc., 1971) 244-245. 42). Brown, City Without Cobwebs, 241-243. YORK: A UNIQUE SOUTH CAROLINA COUNTY By Lawrence E. Wells Editor of The South Carolina Magazine of Ancestral Research For the writer York County is unique because he must go back into the fourth generation of his ancestors (the "great-greats") to find one who was born somewhere else. When Robert Mills wrote his Statistics of South Carolina (1823), in describing the conspicuous features of York District (county), he remarked on the unusual attention paid to the dead. York County was even then noteworthy for the large cemeteries, with most graves marked by stone monuments, adjoining the Presbyterian churches. These picturesque churchyards, at Bethesda, Bethel, Sharon, Bethany, Beth-Shiloh, Olivet, or Smyrna, would still inspire Thomas Grey to write more elegies. On the other hand one finds in York County fewer private family burying grounds. There are, of course, forgotten cemeteries in the woods, but these usually mark the site of a defunct church. The cultural pattern in York County was to bury the dead in the consecrated soil of a churchyard: a considerable boon to the genealogist. When one examines the probate records of York County, it will be noticed that in the pre-newspaper days the Citation to Kindred and Creditors will have a note stating that the Citation was read from the pulpit of one of the churches, with the clergyman's signature. When that bit of data is discovered, by all means go the the cemetery of that church. This is a quick and easy way to locate tombstones. It is also a good way to sort out different families of the same surname, such as the Bethel, Sharon, or Neely's Creek Campbells, or the Bethesda, Beersheba, or Bullock's Creek Loves. York County has an outstanding and virtually complete corpus of county records which begins in the year 1786. One remarkable record group in that court house is the collection of records of the Court of Equity, recently laminated and a joy to use. The settlement of York County, however, ante-dated the erection of the county by nearly two generations, and so it is necessary for the diligent researcher to explore other county records scattered through two states. When the earliest settlers arrived around 1750, there was no boundary established between the two Carolinas. Although the two provinces were disputing their respective claims to the region, the area was generally supposed to belong to North Carolina and to be part of the frontier county of Anson. Anson County, NC still has its seat at Wadesboro, and the Register of Deeds there has frequently answered inquiries by mail. Shortly thereafter, the western part of Anson County was set off as Mecklenburg County, with a court house still in Charlotte, and what is now York belonged to Mecklenburg. Mecklenburg County deeds were published in the 1974 issue of the Georgia Genealogical Magazine, abstracted by Brent Holcomb. In 1768, the part of Mecklenburg west of the Catawba River was cut off to form Tryon County, NC. Tryon soon had a court house located in the present York County, between the town of Clover and the village of Bethany. The approximate site of that court house has a highway marker placed by the York County Historical Commission. Tryon County was eventually abolished and split into the North Carolina counties of Lincoln and Rutherford, and the Tryon County records inherited by the new county of Lincoln, whose seat is still at Lincolnton, NC. The Minutes of the Tryon County Court, which mention many York County notables, are published in the Bulletin of the Old Tryon County Genealogical Society. In 1772, the boundary question was settled and what became York County was thrown into South Carolina. Tryon County lost its court house and perhaps a majority of its population. South Carolina gained a well-populated piece of territory, peopled almost entirely by Scots-Irish pioneers. Within what became York County, there were already four Presbyterian churches, and by the year 1800 there would be four or five more. Although Baptists, Lutherans, Anglicans, and Quakers were nearby in both Carolinas, these groups were conspicuously absent in York County. When York County became a part of South Carolina in 1772, it found itself in a Province of rather different traditions in local government. North Carolina, like Virginia, had from a very early time a system of strong county courts. These county courts, consisting of several Justices of the Peace, or "Gentlemen Justices," would sit together and hold court once a quarter. The Court would record deeds, prove wills, grant letters of administration, bind out orphans, license taverns, ferries, and grist-mills, and compile records of inestimable worth to genealogists. But South Carolina in 1772, a city-state ruled from Charlestown, had only nominal counties, and York fell into the ill-defined hunk of territory called Craven County. Equally meaningless was the fact that it belonged to the Parish of St. Mark's: we may be very sure that the Anglican presence in York County at that time was negligible, if not nil. The only hint of a Church of England clergyman in the pre-Revolutionary York County was the chaplain who accompanied North Carolina Royal Governor William Tryon when he traveled through in the 1760s to survey the Indian boundary. Under the new government of South Carolina, a resident of York County area had to travel to the district capital at Camden to enter a suit at law. To record a deed, prove a will, or obtain letters of administration, he had to make the long trip to Charlestown. But remote from Charlestown as it was, some records from York County were recorded there which genealogist should not overlook. At least two wills written by York County residents were recorded by the Ordinary in Charlestown, those of John Bratton and Charity Kerr. Surely there are more. Under the new regime the area gained a quaint name: the New Acquisition District. Although not all of the territory "newly acquired" by South Carolina through the 1772 survey was part of York County, the importance of the well-settled region between the Broad and Catawba Rivers caused the name New Acquisition District to be used for what later became York County. At the Provincial Congresses of 1775 we find representatives from the "District of the New Acquisition," and the name stuck as late as the State Constitutional Convention of 1790. The importance of New Acquisition District is evidenced by the fact that in the Provincial Congresses it was allowed fifteen representatives, while the "District between the Broad and the Catawba" embracing the territory south of New Acquisition, later divided into Chester, Fairfield, and Richland Counties, was allowed only ten. In 1781, while the American Revolution was still going on and Charlestown was in British hands, Governor John Rutledge appointed Ordinaries for each of the seven districts. This placed a Court of Ordinary in Camden, and for the few years that office existed, Wills and Administrations from York were handled and recorded there. These records finally found their way into the Kershaw County Probate Judge's office and are extant. These neglected probate records of Camden District, in which numerous York County pioneers are mentioned, are currently being published in The South Carolina Magazine of Ancestral Research. We now have a long list of counties whose records must be searched in order to trace an early York County family: Anson, Mecklenburg, and Lincoln in North Carolina; Charleston, Kershaw, and York in South Carolina. And even all that searching is not exhaustive. York County was settled from two directions. There were new immigrants from the port of Charlestown (the McKnights and the Beersheba Loves, for example) and overland pioneers whose backgrounds were in Pennsylvania and Virginia (the Brattons, Guys, Bethesda Loves, Watsons, Henrys, and many others). Therefore the records of many counties in Pennsylvania and Virginia are essential for any thorough search, notably Chester, Lancaster, York, and Cumberland in Pennsylvania, and Orange and Augusta in Virginia. A final observation and a question. York County was one of those South Carolina counties created by the County Court Act of 1785, and that piece of legislation gave the county its name. The 1785 Act was a program to create counties of the kind found in Virginia and North Carolina. The lowcountry region flatly rebuffed the program, but in the upcountry the county court concept took hold and thrived. This was because the people of the upcountry were not only dissatisfied with the inconvenience of having their affairs in mesne conveyance and probate handled in Charleston, but were also experienced with county government in the provinces to the north whence many of them came. David Duncan Wallace has written in his Short History of the "incompetence" of the county courts erected in 1786 and gives this as the explanation of their abolition in 1800, when they gave way to districts, smaller than those districts created in 1769, but set up more or less the same. But, when one peruses the earliest Minute Book of the York County Court, which got right down to business in January of 1786, one is not left with an impression of incompetence at all. The Justices were diligent in being present for court. Several had formerly been members of the Tryon County Court and were experienced in procedure. The clerk, John McCaw, made clear and literate records. In the first year of its existence, the court had established a permanent site for its seat (at Fergus' Crossroads, later called Yorkville), begun a court house, "gaol," and set of stocks, appointed constables for every section of the county, named road managers and ordered several new roads to be laid out. Whatever may have been going on in forgotten counties such as Lincoln, Bartholomew, Winton, or Lewisburg, the York County Court was obviously doing its job effectively. This is the question. It is a firm tradition that York County took its name from York County in Pennsylvania because many early settlers came from the northern county. The only contradiction worth mentioning is an early newspaper article which says the name came from an early settler named Jonathan York, but this seems doubtful. The earliest usage of the name York was in the County Court Act of 1785. Is there any real contemporary documentary evidence for the source of this name? York County, settled prior to 1750, organized 1785, was known as the New Acquisition District, and was settled for the most part by Scots-Irish Presbyterians who came from Pennsylvania and gave to their new home the name of a county in their mother colony. A Presbyterian minister named Richardson, graduate of Princeton, organized Bethel church in 1764 and in 1769, Presbyterian churches were organized at Bullocks Creek, Bethesda, and Ebenezer. The Rev. Joseph Alexander, noted teacher and patriot, was pastor of the Bullocks Creek church. The people of the Scots-Irish county were strong, morally, mentally, and physically. They were industrious, self-reliant, deeply religious, and in their descendants these characteristics are perpetuated. To build an enduring and prosperous nation they perceived they must have school houses and churches. They proceeded to establish them, and their posterity has most liberally maintained these institutions since the county's earliest days. In 1920, York County had a population of 50,536, estimated at 52,133 in 1925, and Rock Hill, its chief town, had 8,809 inhabitants in 1920, but, with those living in the environs, the number is estimated at a much higher figure now. Fort Mill's population by the last census was 1,946; Clover's people numbered 1,608; Hickory Grove had 301; McConnells, 247 ; Sharon, 419 ; Tirzah, 160 ; Smyrna, 101. York, with 2,731 inhabitants, is the county seat and is a town of rare and distinctive beauty, so visitors say. In the Carolinas is no other town like York. The county has 651 square miles. North Carolina borders it on the north, the Catawba river runs through its northeastern side and forms its southeastern boundary. The Southern Railway, Seaboard Air Line Railway, and Carolina & Northwestern Railway, with a total of 101 miles, traverse the county. It has nine accredited high schools. Its fertile soil yields an annual average of 30,000 bales of cotton, and an abundance of wheat, oats, rye, corn, peas, cane and other crops of the Piedmont country. A number of commercial peach orchards have been planted and promise to be lucrative. The Wateree Power company on the Catawba River and the Southern Power company at Great Falls and at Ninety-Nine Islands furnish abundant hydroelectric power not only for manufactories now operating but sufficient for great and progressive expansion of industries. One million dollars has lately been expended for the construction of 45 miles of hard surfaced roads and another million of bonds has been voted to complete the hard surfaced county system, and the topsoil roads are extensive and well maintained. Last year 15,319 children were in the public schools, of whom 8,225 were white and 6,994 colored. Every year $400,000 is used for the maintenance of these schools and the value of the school buildings in the county is in excess of $1,000,000. No county in South Carolina has a citizenship of sturdier virtues and greater intelligence. Along its northwestern border runs the Kings Mountain range and the Kings Mountain battle field and battle monument are in York County's territory. Ancestors of many York families fought in the battle and many another engagement of the Revolution. Their virtues live in their sons. Immediately above, published in "South Carolina: A Handbook," prepared by The Department of Agriculture, Commerce, and Industries and Clemson College, Columbia, South Carolina, 1927. In the Public Domain. [with minor edits] |

|||

|

|

© 2021 - J.D. Lewis - PO Box 1188 - Little River, SC 29566 - All Rights Reserved